JEANIE FINLAY: A Creative Approach to Audience Connection

By Barbara Twist

In this conversation with Jeanie Finlay, we discuss approaching a film with an artist’s mentality, focusing on authenticity and creating experiences that extend beyond the film: all in the name of audience connection. From her earliest works, TEENLAND and GOTH CRUISE, to her latest film, YOUR FAT FRIEND, Jeanie has approached them with her participatory philosophy, ‘it’s all the work’ and embraces the idea that everything touching a film is part of the creative work.

You came into making films as an artist, and you’re directing & producing your tenth feature film right now. Can you talk about your evolution as a filmmaker and how your art-making practice informs your work?

I've been thinking and writing a lot at the moment about where I sit in my career. Lots of thoughts I've had across my practice are finally coalescing. They’ve come to a crescendo on YOUR FAT FRIEND in a way that makes me feel that I can do this. I’ve finally arrived at a point where I know how to do this.

When I was practicing as a visual artist, my side hustle was doing graphic design and branding for companies, helping them to tell their story. Early on, I embraced the idea of ‘it’s all the work.’ As an artist, everything you touch is the work. The audience for your film may actually be the people who only see your trailer or poster. Realistically, many, many more people will see your marketing materials than actually see the film. That could seem disappointing, but if you embrace everything that touches your film as the work, then it can become a really fun and creative opportunity.

My first film, TEENLAND, was commissioned by the BBC. It’s a documentary about four teenagers living their separate existences inside their bedrooms all day long, isolated from the rest of society. I was six months pregnant, and I had been in development for a year prior to that. I'd made, by accident, an interactive documentary called HOME-MAKER that had gone viral in the early days of the internet. I was hand-coding websites and creating interactive environments in the living rooms of older people who were housebound in Derbyshire and then Tokyo. I started filming because the conversations I was having with people as I photographed them were actually the work. They were the essence of the thing. So I picked up a camera and I learned by doing.

TEENLAND got into just one festival, Big Sky Documentary Film Festival in Missoula, Montana. It was there that I had this transitional moment where I saw an audience watching my film and realized I loved the response. There was something about the immediacy of the audience that is completely invisible when you make work in a gallery. After a gallery opening, the only thing you’d get is the visitor's book. I decided I’d rather be an arty filmmaker than a filmy artist. Around this time, I attended one of the first BRITDOC festivals, which was really important for me in terms of forming my identity as a filmmaker. I felt like this wide-eyed stranger arriving, a noone from nowhere with my 60-min film TEENLAND, talking to all of these very confident people. And then I realized I had completed a film when many others hadn’t got past the pitching stage and I left feeling more confident.

My second film, GOTH CRUISE, was commissioned pretty quickly after that. The documentary follows 150 pale, ‘people in black’ on a boat, taking part in the absolute antithesis of Goth – a cruise in the blazing sunshine, as they sail around Bermuda for five days on the 4th Annual Goth Cruise. The experience was a baptism by fire - running two units across a huge ship in the Atlantic, working with a production company, notes and the challenges of delivering for an American channel. I learnt so much and it helped define how I wanted to approach production going forward.

I soon set up my own production company, Glimmer Films, because I knew that I wanted to make films with care - care for the people in front of the camera, care for people behind the camera. I wanted to set the schedule so I could have a longer edit. I wanted to be able to pick collaborators that chimed with that, and I wanted to be in the room when production decisions were made.That doesn't mean that I don't want to play with everyone else. I want a big team, but I want to be driving the bus, because that's my happy place. I like being in charge. I like setting the tone and saying, 'These are the rules of engagement. This is the budget. This is how we’re going to make the film.' I called it Glimmer, because I'm always looking for that tiny something - the glimmer of a moment that only happens because I've lifted a camera with that person, in that moment, at that time.

That desire to be in charge, to believe that ‘it’s all the work,’ how did that inform your approach to distribution and audience building?

TEENLAND had played Big Sky, but it also had a successful BBC broadcast and loads of press. It was the Pick of the Day in every newspaper. I also built a website for it, did print, and it felt fully launched. And then GOTH CRUISE went out through IFC in the US. We did a screening in London, but it didn’t have a meaningful festival run. It made me realize that if you don’t have an audience strategy, you miss the opportunity. It would be like making an artwork, but you never get to show it to anyone. I discovered I really needed the public-facing engagement to feel like the film was complete.

I had met Gary Hustwit through BRITDOC and was really fascinated with how entrepreneurial he was about his audience. He described taking his film HELVETICA on the road, booking out design venues and schools independently, and I was inspired. That’s what you would do if you had a gallery show or a book tour; you dream what you want to do and you make it happen.

With my film SOUND IT OUT, a documentary portrait of the very last surviving vinyl record shop in Teesside, North East England, it was very grassroots. The BBC passed on the film, saying it was too small but I knew that the smallness was the charm of it and if I ended up pitching the film for 2 years, I would lose the love I had for it. I just wanted to make it - so the film became one of the very first crowdfunded films in the UK.

It premiered at SXSW which opened up huge opportunities for the film - we ended up releasing it in New York. That led to a theatrical release in a few countries and by the time we brought it back to the UK, we took the film out on the road like an indie band. We had vinyl parties, record pop up shops, and played at music festivals. It was the first film where I had this really direct connection with the audience and I kept questioning how the storytelling of the film bleeds into the world.

My background as an artist informs my love of multiples, special, beautiful things you design, to fit exactly how you want them to be. I had a meeting with a distributor about the DVD, and he was a right old wise guy. He said, 'I'll take your film, I'll stack them high and sell them cheap.' I was horrified. My emotional response to what he said solidified for me that what I wanted to do was make a double seven-inch gatefold DVD with a baby blue vinyl soundtrack. They’d be limited edition, so they would be cherished in peoples’ record collections. We distributed them via the Record Store network in the UK and they were released and screened in independent record shops on Record Store Day across the world, as well as The Lincoln Center. And then the BBC bought the film after all.

You made a film, ORION: THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING, about a mysterious Nashville singer whom hundreds of thousands of people believed was Elvis back from the grave. He wore a mask to hide his real identity and had a voice that sounded just like Presley’s. He became beloved in the South, selling more than a million records, and playing to large audiences. Given that you had this large potential fanbase, how did you connect them to the film?

We approached them in a few ways. We worked with a media scraping tech company called Tint to help us collect digital archives of fan mementos. By using the hashtag #MyOrion, the audience and fans were able to share old photos and mementos from concerts, and we were able to gather those memories and follow up by phone. It was a way where we could include the audience in the making of the film and give them a way to show off what they had.

We knew ORION's fans were older people who lived in the South and were on Facebook so we also did research through Facebook. We would post questionnaires with an incentive. We made phone calls. We interviewed people. There are lots of ORION interest groups. I put in an enormous amount of work to gain entry and be trusted. My strategy was to identify who were the leaders and most chatty people in the groups, and go to them first. What I’ve learned is to always bring the activity or the work to the places people live. It works really well because you’re finding out where the audience lives, whether it’s Instagram, Facebook or whichever social media, or offline social spaces, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel.

With your films, you have this ability to create an experience that expands beyond the screen. Dr. Judith Aston calls your practice ‘wrap-around artworks.” Can you dig into how you use artwork inspired by the film to deepen the connection to your audience?

When we were researching ORION, I brought on board Dr. Lucy Bennett, who is an academic focused on fan studies. What I learned from her is that in fandom, it’s not the relationship you have with the person who is the object of the fandom (i.e. Orion); it’s finding community. It’s finding each other, the fellow fans.

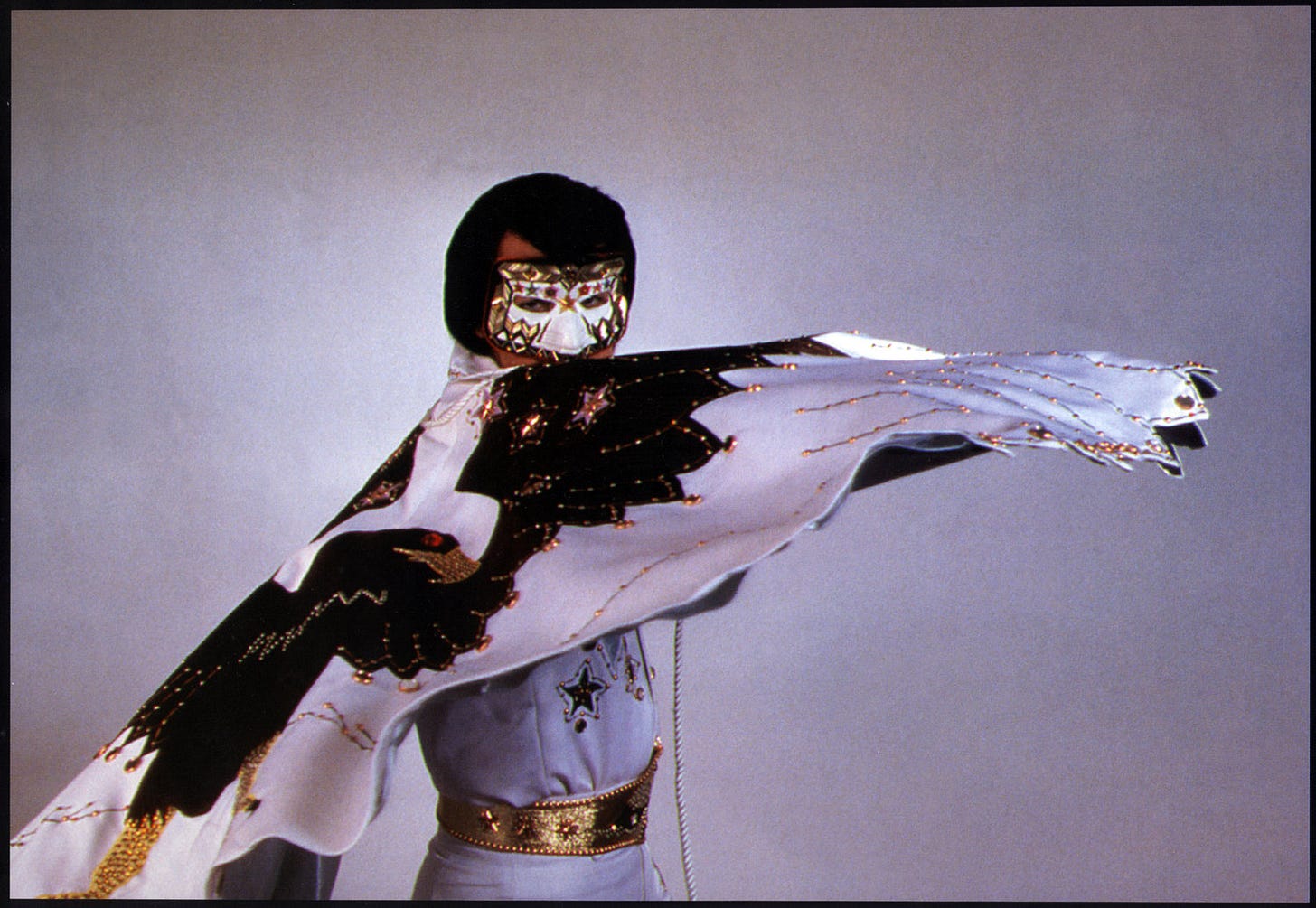

With ORION, I created a wraparound artwork called ‘I Am Orion.’ We recreated the masks from Orion’s iconic album covers and then we gave them out to audience members. On the inside of the mask, there was the hashtag #IAmOrion with the question, ‘Would you wear the mask?’ I wanted people to wear the mask and think about what it felt like, knowing that Jimmy Ellis wore the mask to become the mythical singer Orion. It was transformative but also a cage. People used the hashtag when they posted their photos and it allowed us to locate and then display them online. The release snowballed and we had guest Orions in every town performing at screenings, at a huge gala screening in Bristol, performers dressed as Orion abseiled down a building. Really. Even Jimmy Fallon ended up wearing the mask!

With THE GREAT HIP HOP HOAX, I re-drew by hand those fortune teller fish as lie-detector fish and had them printed as a multiple. You could only get one at a screening and I handed them out in person. With YOUR FAT FRIEND, we did gold stickers. I’ve always done stickers because I like the long tail; people take it home, they put them on their wall. As an example, I was making a film called INDIETRACKS and I wanted a particular piece of music for the film. I saw the band ‘The Just Joans’ play and after, I went up to them to ask if I could use their music in my film. David, the singer pulled out his wallet, showed me his SOUND IT OUT sticker he’d got a year before, and said, ‘Yes, you can use our music.”

As an artist who makes films, everything that touches the film bleeds out into the world and continues long after the credits roll. If you make a beautiful print and someone puts that on their wall, that lasts for a really long time. It's a deep, meaningful connection in people's lives. I like interrupting the tech algorithms by making things by hand, making them special. At a time of AI slop, that hand crafted touch feels like rebellion. The street art is the film. The sticker is the film. The hand embroidered opening titles to my Game Of Thrones doc is the film. It’s all the film. It’s all the work.

Your most recent film is YOUR FAT FRIEND, starring Aubrey Gordon, a writer and co-host of the popular podcast Maintenance Phase. When you met her she was an unknown anonymous writer, writing for free and you were working on a different project, LUXURY BITCHES. How did that meeting with Aubrey come about and when did you know she was your subject?

I’d had development money for LUXURY BITCHES from Broadway Cinema (my base in Nottingham) and spent roughly a year developing a film about perceptions of fatness. I’d met a lot of plus-size bloggers; they were fabulous but there was too much focus on clothing and surface. . I couldn’t find the specialness, no heart or emotion. No story.

But I stuck with it. I was in Los Angeles for my documentary GAME OF THRONES: THE LAST WATCH and flew to Portland because there’s a big fat scene there. I spent a few days filming a dance troupe and meeting up with a few different people. I’d contacted Aubrey, who lives in Portland, because I read the first piece she wrote as her alter ego Your Fat Friend. I was intrigued that like Orion, she was anonymous, that she was dealing with small, relatable emotions and her writing was candid and poetic, and I had no idea what she looked like, because she was an avatar.

I met her on the last day of my trip. I remember her opening the door and giving me a massive hug. She knew who she was and wasn't afraid of that. She was just so charismatic. She showed us around the house. I got her to sit at the table in her kitchen and read out her essay and her voice changed. She became quiet and serious and contemplative. On the next trip we filmed Aubrey and her mum in the kitchen together. Her mum found the conversation very challenging. Her dad couldn't say 'fat' out loud and her mum just seemed like this deep well of emotion. It was a deep contrast with Aubrey’s desire to change the world and between those two things, I felt there was a space where a film could live. I knew she was the film.

Aubrey is now a well-known blogger and podcast host with a huge audience. How did that factor into your distribution strategy for the film? Did you have a sense that the film would resonate with so many people?

We didn’t expect it at all. I'd been filming her for a few years when she started making the Maintenance Phase podcast. YOUR FAT FRIEND, as well as with GAME OF THRONES: THE LAST WATCH and SEAHORSE, were all films made in secret. Initially, my expectations were that I'd made a small, weird, niche film - for myself, and I was completely wrong.

We started the mailing list and launched the Instagram account the day that the Tribeca Film Festival announced they had programmed the film. I chose the images very carefully because I wanted them to be really impactful. I had a relationship with this rock star photographer, Joseph Cultice, and I knew that I needed Joey to light Aubrey with luxury – to make her look like a rock star.

We launched with a collaborative post between Aubrey and the film, and my phone – I’d never seen anything like it. People were losing their minds. We did a countdown for buying tickets and they sold out immediately. Tribeca had put us in a really small cinema and we tried to warn them that the premiere was going to be really popular, that Maintenance Phase has 1.2 million listeners just in NYC, but I don’t think they really believed us. When the screening started selling out fast, they moved us to a bigger venue. People flew in from other countries to see the film. When we showed at Sheffield DocFest, we sold out the Crucible Theater, which is a legendary venue, with people flying in from Europe to watch the film.

I would caution here though that Aubrey’s following was just the beginning. What we developed was a reciprocal conversation with the audience and listening to them really shaped what followed.

After your UK and limited US theatrical releases, you partnered with JOLT to maximise the rollout to online audiences and to really learn about them. How did you bring your ‘it’s all the work’ care to the social media content?

I saw Gerilyn Dreyfous talking about Jolt on a panel and I contacted them and said “we could learn a lot from each other”. At that point we had released to cinemas across the UK and generated six figures in online screenings, all through an advertising spend of £0. Everything we had created was organic, instinctive.

Jolt was an opportunity to discover how paid, targeted advertising and deep audience insights could really “jolt” a release. Could we uncover an audience that is way out of our hands as independent filmmakers? Consulting Producer Suzanne Alizart and I are always hungry to learn new things, and the transparent data that Jolt provides to filmmakers is really a rare look under the bonnet. We had protected our rights on the film - could we maximise their potential?

It was important for me to place a brilliant fat lady (Social Media advisor Dor Dotson) onto their team who would not only be tenaciously creative but also deeply understand the needs of the audience and what had worked prior.

It was a lot of work as we were posting unique content every single day but it also meant we now had a team, so instead of just me and an assistant, there was Dor, a designer, and the whole Jolt team. And we were having a very direct, responsive conversation with the audience. That is, I believe, what really helped us to break out and we’re their most successful film to date.

Once our initial period on Jolt ended, and we weren’t feeding the machine as intensely, the social engagement definitely dipped. When filmmakers think about the life of their film, I’m not sure how much they’re thinking about the volume of content needed. You might have one good image, but have you got 20, or 100?

Dor was amazed though at the traction we’ve been able to maintain. She thought the “fat” content might be problematic for the platforms as the word can be seen as a slur, but we appear to have gotten into a sweet spot where we’ve trained our algorithm for the YOUR FAT FRIEND account plus Aubrey’s and my accounts. They know we will use the word fat in a neutral way. In contrast, our composer Tara Creme went to post about the broadcast and wrote ‘Yay, YOUR FAT FRIEND film is on tonight,’ and she immediately got a content warning about offensive language from Meta.

We’re back on Jolt again, one year on and learning more new things ahead of our streaming release later in the year, which will be boosted by the deep audience insights we now have.

I often think about what’s coming up and how I can riff on that. I also think about how to lean into the parts of the movie that are difficult. When I knew the broadcast on BBC Storyville and CBC was coming up, I wanted to prepare the audience a bit. The film would reach people we’d never reached who might not be as comfortable with the content.

I licensed a series of writings by Ragen Chastain “What to say at the doctor’s office” and designed them as printable cards. A practical, fact-laden set of support cards for the fat audience for the place where they can experience the most bias.

When we put the film out in cinemas, I was concerned that people would think that Aubrey had invented fat politics and activism. She’s coming in 30 years down the line, so one thing we thought would be an approach to acknowledge this would be to have a fat reading list on the website and to partner with independent and queer bookshops wherever we showed the film. We asked them to come down to our screenings and set up mini bookstores in the foyer of the cinema, lifting up other’s work.

We were also asking fat audiences to sit into potentially small seats, so we made every venue showing the film think about seat size as an access issue - asking them to measure and publish their seat size. We can’t make the seats bigger but we can give people the information they need to make a choice.

All of these interventions were designed in response to what the audience for this film needed, in this moment, to really land.

I really hope that anyone reading this is prompted to think about the questions that their audience is asking rather than “Got it - watch parties and Jolt are the answer.”

Given Aubrey’s following and the response you saw from your festival run, it’s disheartening to know that traditional distributors didn’t step up. How did you fund the release without that piece?

We turned down the paltry and disappointing offers from distributors, that is, the ones that got back to us. The offers were pretty standard but honestly insulting and did not reflect what we thought was the commercial value of the film. I also didn’t think they were going to do a good job because I didn’t think they understood our film. They were scared of the subject matter. We also weren’t able to raise money to take the film out on the road through traditional routes. Instead, we built up a reserve. We did three Kinema watch parties. The first one made enough money to allow us to release in the US at DCTV in NY to qualify for the Oscars. It was a global watch party and we did it as a drop. We made it so if you joined our mailing list, you got access to the tickets, and we doubled our mailing list overnight. We told people two days before the watch party tickets went on sale. I think it sold out in 40 minutes. The second watch party paid for our UK release in cinemas. We toured twelve cities in a sold out live preview tour and then went wide to over 100 cities, with many booking week runs. We were the number one documentary at the UK box office

I think we spent around £40-50,000 to cover the usuals: marketing, DCP creation, our great theatrical booker Tull Stories, PR, and trailer. We also wanted to pay for ethical transport for Aubrey. I wanted to bring Aubrey over in comfort and as a fat lady, that means business class travel, taxi from the airport and a car. We also brought on a project manager to take us around the UK, but our merch sales paid for that.

You mentioned you qualified for the Oscars. Did you raise money for an awards campaign?

We had a meeting with our brilliant PR person who launched our film at Tribeca where he told us if we wanted to get an Oscar nomination, we needed to reserve $5,000 to send out just five ‘For Your Consideration’ emails and that we needed to have a party. It just seems immoral. It’s throwing money in a well. I knew we weren’t going to get an Oscar nomination. We had no studio behind us. We didn’t premiere at Sundance. If you look at the stats, those are the films that get nominations. So instead, we spent that money on artist commissions to make beautiful merch where we could pay them fairly and share those pieces with the fans.

I think so often there’s a desire to make the film and move on to the next one. Listening to you describe your process – there is something really beautiful and very deep about taking a film and caring for its cultural long tail, digging in to explore every shade of what this idea could be.

When I was a baby artist in my first week at university, I was on a contemporary art degree. We had to make a piece of work to introduce ourselves to the rest of the cohort. The piece I made was a tiny flyer with my face peeking through a hole and it just said, ‘Hello.’ I gave them to my course mates but then I stood on the street and handed them out to members of the public.

I feel like every piece of work I’ve made since then, whether it’s a film or an artwork, is about a small moment of human connection. It’s just now I can connect with millions of people.

Jeanie is releasing the detailed case study of the radical creative distribution of Your Fat Friend by Glimmerama in a series of online chapters - join her mailing list to find out more.

Jeanie Finlay is a British documentary filmmaker and artist known for intimate, award-winning films that resonate globally. Her latest, Your Fat Friend, premiered at Tribeca and won the Audience Award at Sheffield DocFest. She has directed for HBO, BBC, and IFC, including four BBC Storyville films including The Great Hip Hop Hoax and Orion: The Man Who Would Be King.

Her work spans subjects from a transgender man’s pregnancy (Seahorse) to the final season of Game of Thrones in her Emmy-nominated The Last Watch. Her work is known for its emotional intimacy, pathos and humour and has garnered Emmy, BIFA, Grierson wins and nominations as well as an inspiration award from Sheffield Doc Fest and an honorary doctorate from Nottingham Trent University.

A champion of creative distribution, she’s a Chicken & Egg Awardee with retrospectives at Criterion, BFI, and MOMI NYC, True Story and Big Sky Documentary Film Festival. Jeanie is a member of AMPAS, BAFTA, and FWD-Doc and is currently making her tenth feature. www.jeaniefinlay.com / @jeaniefinlay

Wonderful interview as always! Thank you for sharing Jeanie with us.

It's so awe-inspiring and empowering to experience Jeanie's ethos, values, and principled approach not just in making the film, but also stewarding resources and connecting with audiences. Two powerful leaders in the field, having an important conversation here. Thank you Rebecca, Jeanie, and Barbara for sharing this with us!